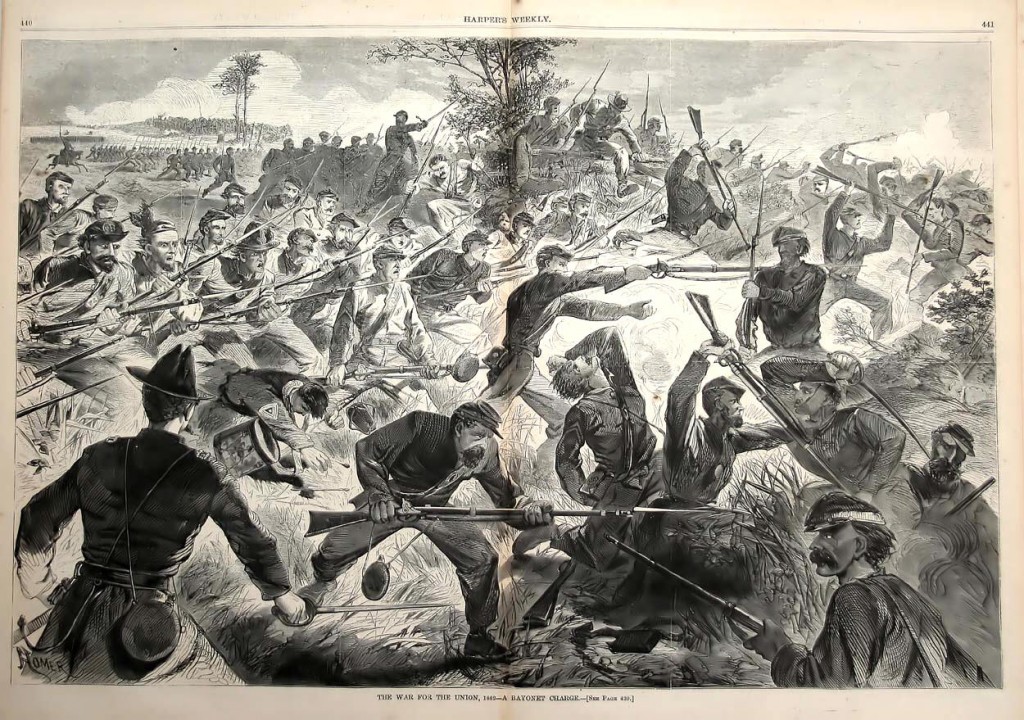

I’ve read it countless times in soldier’s letters, “I saw the glistening bayonets of heavy masses of infantry…” or something to that effect. The impact of seeing a brigade (or larger) of the enemy in their front with bayonets fixed cannot be overstated. However, there is some debate as to the use and effectiveness bayonets had on combat during the American Civil War. For example, The 1870 Surgeon General’s Medical and Surgical History of the War of Rebellion (1861-1865) on Civil War listed wounds treated in Federal hospitals and it reported fewer than 1,000 bayonet wounds.

Most often the order to fix bayonets came once a unit’s ammunition supply was exhausted and the only option left was to charge, “We were now nearly out of ammunition , some having fired the last round. The order was given to fix bayonets…” [1]. Sometimes during a chaotic fight waves of men would charge back and forth, “They would alternately advance and retreat, charge bayonets, advance and form new lines of battle, change their front,” wrote a soldier in the 13th Iowa. [2]

Robert Cruikshank of the 123rd NY Infantry was at Gettysburg on July 3rd and described a charge he was involved in: “We advanced into the woods and in the rear of the 20th Conn. where we could see our works, when the order came to charge. The men began to cheer and run forward, firing as they advanced, bayonets fixed. The battery ceased firing. On we went over the dead and wounded; the enemy falling back, we soon reached our works and held them. The rest of the Brigade advanced and took their old places in the line and the gap from Spangle’s Spring closed.” [3]

Yet another soldier describes a perilous charge: “… we waited for nearly an hour while sharp shooters in the treetops beyond the peach orchard kept picking off our men our orders were to save our ammunition and not to fire a shot then came the command to fix bayonets and charge the rebel lines then we climbed out of our ditch and made a wild rush for the rebel lines the air was alive with whizzing bullets and the wild shooting of the enemy tore up the sand and filled our eyes with dirt we reached the rebel lines without firing a shot and strange enough we lost but a few men killed and wounded on our side the retreat of the rebels was complete” [4]

The utility of the bayonet was primary as a last result or to repulse a charge by the enemy. When we think of a bayonet charge, of course, Little Round Top comes to mind. But there were other charges that played important roles in their respective battles. One being at Battle of Opequon (Winchester). There the 8th Vermont was involved in a key bayonet charge and here is how it was described:

The First brigade, having repulsed the foe in their own front, have moved back to the woods as a reserve, and the Eighth Vermont and Twelfth Connecticut are now alone on this advanced line. Upton’s troops of the Sixth Corps are on our left and rear, with quite an interval between us. It is three o’clock. The enemy are pressing out towards us from the woods in front. At this moment, some distance to our right and rear, great cheering is heard, and we discover a body of troop., advancing in magnificent array in solid column, with banners flying aloft, and moving rapidly up, with intent, as we suppose, to take position on our right as reinforcements to our thin line. It is Colonel Thoburn’s division of Crook’s corps, and as the solid column advances, the terrible flank fire from the enemy in our front mows them down like grain, leaving literally a swath of dead in their wake. Colonel Thomas is not idle. The moment the enemy’s fire is turned away from us, he makes a daring move on the checker-board of war. He sees an opportunity to hurl two veteran regiments like a thunderbolt against the enemy, which is concentrating every available gun to break Crook’s exposed flanks. “Boys,’1 says he, “what we can’t give them for want of powder and ball, we’ll make up in cold steel. Fix bayonets!’ It gives one a peculiar sensation to hear the sharp rattle of steel, and the whole scene changes. It is ugly work, but the regiment is up and ready for the conflict. Colonel Thomas walks in front of his own regiment and talks tenderly with the men, as though they were of his own flesh and blood. He passes down in front of the Twelfth Connecticut, whose colonel has been killed, and asks the officer in command if he and his men are ready to join the Eighth Vermont in a bayonet charge. Many of the men respond by springing to their feet. The captain explains that his ammunition is exhausted. “So is mine.” said Colonel Thomas. “Three times my regiment has fired the last cartridge.” ”So has the Eighth Vermont,” said their gallant old leader. Then walking back, he determines to lead his own regiment to the charge, and leave the others, believing they would follow. He moves forward, holding his sword high in air. His faithful men spring to the line, their bayonets glistening in the sunlight. The Twelfth Connecticut, inspired by this courageous dash, soon follow, and the enemy are driven at the point of the bayonet from their works in the timber, our own regiment capturing scores of prisoners who could not get away, so sudden and desperate was the assault. In vain do staff officers and General McMillan himself ride furiously after the men, shouting to Colonel Thomas to halt his lines the brave old commander—God bless him!—is riding with drawn sword, in front of a line of steel bayonets, and cannot be reached. Nor do they halt until the colors they bear are planted on the open plain in sight of Winchester. Not a Union flag to be seen in the wide sweep to the left, not a Union flag in front, not a Union flag to the right; only rebel flags and batteries, one above the other, with infantry massed between, frowning down upon us, who are amazed at the grandeur of the scene. The regiment awaits the next order, while their leader hastily scans the held, which at that moment his men hold in sole possession.

A flash, and an angry roar and a horrid screeching sound is heard, as a shot tears through the air a few feet over our heads, and then we discover immediately on our left and front two pieces of artillery. The enemy we have driven back has retreated to the battery. Quickly Colonel Thomas orders the regiment to double-quick to the tall trees ten or fifteen yards to the left, form on the colors, and give them a volley. In scarcely more time than it takes to write it, the regiment obeys, and the order to load and fire is accompanied by a queer remark about “riddling their shirts.” It is literally carried out; lor the volleys which follow instantly silence both pieces, and sweep every sign of life from the guns. Among those killed here was Charles Jenks of company I. When the line reached the timber, where the enemy’s dead and wounded were lying as they had fallen, showing the effect of our rifles, the attention of the regiment was attracted to a strange scene;—a dead rebel lay stretched on the ground and in front of him sat a little brown dog, trembling with fear, bolt upright but facing square to the front, faithful unto death. Not a bayonet or a foot touched the faithful creature; the line of steel parted and the human wave rolled on through the woods, leaving the little sentinel undisturbed in his death-watch.

This exciting affair is hardly over when white puffs of smoke dot the plain, and a storm of iron hail is rained upon our uncovered heads from guns planted further up the plain, one above and back of the other, and from different points, which bids fair, for a few moments, to completely wipe us out. But the Twelfth Connecticut has joined its on the right, and the advance lines of Crook’s corps are rushing in from the same direction. Plunging shot and shell are creating terrible havoc in the tree-tops over our heads, when a Union flag bursts from the woods into the opening on our left; then another and another, and the plain for a long distance to our left swarms with Union troops of the Sixth Corps, the flags and regiments appearing en echelon, while almost at the same instant the cannonading concentrated on us is suddenly distributed along the whole line.

Now we realize for the first time how far the rushing bayonet charge has carried our regiment in advance of the main army. Meanwhile General Upton of the Sixth Corps, whose men are coming up on our left, rides up through the regiment and engages in hasty conversation with Thomas, concerning troops obscured by smoke still further to the left. When the cloud-wreaths lift, and we catch sight of the familiar southern cross on the enemy’s battle flags, the colonel orders the sights on the muskets raised, and one or two (puck volleys are fired upon their confused lin-^s. But our flanks are now up, and with infantry in front, cavalry and infantry on the enemy’s left flank, with one grand rush the Union troops close on the Confederate army, and the finishing charge is sharp and crushing. Brave Colonel Van Petten, although wounded, moves to the right of the Eighth Vermont with the One Hundred and Sixtieth New York, and connecting with the right of Upton’s troops, we advance rapidly toward the enemy’s left centre, in the direction of their retreat, delivering an enfilading fire as we advance, and receiving in turn a heavy artillery fire. Men from Ciook’s corps, without any formation whatever, join us till we come to a stone wall, passing the bodies of the dead artillerists. But the enemy’s artillery breaks down the wall, the stones of which flew in all directions under their fire, when we move back a few yards and then charge over beyond; and by this time the entire rebel army is on a race for life, and soon after Sheridan is able to telegraph to the war department that he has sent the enemy ” whirling through ‘Winchester,” and that “this army fought splendidly.”

Horace Greeley, in his carefully prepared History of the Great Civil War, has singled out this bayonet charge as one worthy of special mention, for its national importance.

[5]

Add One