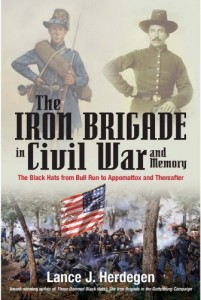

This interview would not have been possible without the help of the fine folks at Savas Beatie publishing. Lance Herdegen is the former director of the Institute of Civil War Studies at Carroll University. He previously worked for the United Press International (UPI) news service covering national politics and civil rights. He presently is an historical consultant for the Civil War Museum of the Upper Middle West. Mr. Herdegen is the author of numerous books on the Iron Brigade, most importantly and recently, The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory (2012).

Q: Lance please tell me a little about your background? I grew up in rural Wisconsin and earned a journalism degree from Marquette University in Milwaukee. I joined United Press International (UPI) wire service and worked in the news business for almost 30 years. As was the custom, over the years, I covered almost every type of story while a reporter and editor, mostly civil rights and politics. It was the best place to learn how to write quickly and tell a story and it also provided quite an education beyond the classroom. When UPI began to have difficulties, I went to Carroll College in Wisconsin as public relations director. The school had a wonderful Civil War collection and I hoped to use it in my Civil War research. That led to creation of an Institute for Civil War Studies. I served as director of the institute and taught Civil War classes until I left Carroll. After that, I worked on a team developing a Civil War Museum at Kenosha, Wisconsin, which is located between Milwaukee and Chicago. I still serve as a historical consultant for the museum as I continue to write about the events of 1861-65. My first book, In The Bloody Railroad Cut at Gettysburg (with William J.K. Beaudot) was published just about the time I joined Carroll and left UPI. What a strange career path it has been

What drew you to The Iron Brigade? One may describe it as an obsession, which is perfectly okay. It is difficult to grow up In Wisconsin and not develop an interest in the Iron Brigade. It probably began when my dad brought home an 1864 dated Colt rifle-musket he found while helping a neighbor clean an old shed. I was totally fascinated by the antique and began to read everything I could find about the Civil War. That led me to the Iron Brigade and the realization there was this famous unit with ties to my home state. There were three Wisconsin regiments in the brigade (along with one each from Indiana and Michigan) and the soldiers came from towns and farms around where I live today. I joined the North-South Skirmish Association to learn to shoot my old musket and the interest kept growing. When I got in the news business, I was already thinking about writing something about the Civil War and the Iron Brigade was a likely topic. About the time I graduated from Marquette, the late Alan Nolan was publishing his book on the Black Hats. I provided some minor research and we became lifelong friends. I spent many a pleasant day walking the fields with Alan and I miss him. He pretty much finished his history after Gettysburg and several years ago I began thinking about a full history of the brigade—from Bull Run to Appomattox. Ted Savas and Cap Beatie at SavasBeatie were very encouraging and the result is The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory: The Black Hats from Bull Run to Appomattox and Thereafter. I was also fortunate because much new material had surfaced in the 50 some years since the Nolan book was published. For example, some 300 letters from a lieutenant in the 6th Wisconsin recently surfaced in Texas and were donated to the Wisconsin Historical Society. As for why the Iron Brigade, I use the unit to examine my own interest in the larger themes of the war such as the reaction to slavery, leadership, and even how memory affects an individual’s decisions.

You wrote the book chronologically, obviously a must, and also by year thematically, did you come to the structure of the narrative early on in the writing or did it find itself as you researched and wrote? That is an excellent question. The form of the book developed very early in the writing and the larger breakout by year seemed to place the story in better context. As an old news writer, I also tend to write in shorter lengths. The result was large sections (by year and thereafter) with a series of very short subsections within each section. It makes the copy easier to read and shape and that is a device I learned in the newspaper game. (I can’t believe I just used the expression “newspaper game” just now.) It is hard to read through large blocks of type. The subsections also allow a writer to use paragraphs and breaks to emphasize and advance the narrative. I give a lot of thought to pacing within the story. I also try to turn the historical figures of the Iron Brigade into real people who are caught up in what Lincoln called “the fiery trial” of determining the fate of the Union and the nation.

“The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory” was clearly a massive undertaking, was there a moment when you knew you had to tell the story of the whole unit and not just parts? How long ago and how long did it take to complete? The lingering thought of a new and full history of the Iron Brigade began sometimes after the first book the charge on the railroad cut at Gettysburg. I wrote a couple of books about narrow Iron Brigade topics (The Men Stood Like Iron and The Iron Brigade in the Gettysburg Campaign) and edited two others involving the writings of two veterans, one in the 6th Wisconsin and one in the 7th Wisconsin. They built on Nolan’s 1961 book and involved some of the new information that was surfacing. Along the way I kept finding material on 1864 and 1865 and even the reunion movement involving the Iron Brigade Association. About seven or eight years ago, I went through the box of information where I kept throwing the new found information and began seriously thinking about a full history. I got a start, then other work got in the way, and I finally went back to it with a full effort some four years ago. You never really know where the narrative is going until you are actually writing and I was struck by how different the story of the Black Hats became after Gettysburg. They lost their all-Western status, the 2nd Wisconsin and 19th Indiana leave the ranks, the 24th Michigan (which arrived after Antietam in October 1862) leaves in early 1865, and finally, the 6th and 7th Wisconsin soldier on in a war that is so different from 1861 to 1863. It also involved a different kind of bravery. I found the late war very compelling. I think readers will do so as well.

The book is filled full of firsthand accounts by the soldiers. About how many letters did you consult? How many did you find that no one else had seen? What was the research like with regard to unearthing all this data? In addition to newly surfacing material, one of the best resources was found in the weekly newspapers of the time and later. Almost every regiment had a soldier correspondent who penned the news for the folks back home about what was happening the first months of the war. As newspapers were not censored, the accounts give a fresh and unblocked view of the feelings of the volunteers. After the war, the veterans gave long interviews to hometown newspapers on the anniversaries of the various battles. One great source was The Milwaukee Sunday Telegraph, a newspaper edited by Jerome Watrous of the 6th Wisconsin. He used two pages each week to follow the reunion movement and print the stories being sent by the veterans. It was like sitting around a campfire listening to the soldiers themselves. The memories were probably romanced a bit long after the war, but the reminiscences carry a certain style and tone that tell much about the volunteers themselves; how they remembered what they accomplished, and, in a way, how they still walked in the shadow of a war they fought when they were young. How many firsthand sources were used in the writing?–literally dozens. For example, on just the charge on the railroad cut at Gettysburg, I was able to find 45 eyewitness accounts, some written shortly thereafter and some years later.

When did the unit take on the name “The Iron Brigade” and/or “Black Hats.” And can you explain the differences between the unit as The Iron Brigade of the West and how it came to be just The Iron Brigade? Why didn’t they keep it as an all western unit? The name “Iron Brigade of the West” began to circulate around September 1862 shortly after the battle of South Mountain. George McClellan claims he gave the unit the name, making a reference to “men of iron” while watching the Western brigade advance up the National Road toward Turner’s Gap. A newspaper reporter from Cincinnati was with McClellan and in writing about South Mountain a week later made a reference to the losses of what he termed “the Iron Brigade of the West.” The name “Black Hat Brigade’ was used earlier when the four regiments were outfitted with the Model 1858 black felt dress at the Regulars after the grey state uniforms were replaced in 1861 and early 1862. The distinctive hats made the brigade recognizable from both sides of a battle line. The Wisconsin, Indiana and Michigan boys liked the hats. Some two-year New York brigades first used the “Iron Brigade” name after an officer claimed they were made of “cast-iron” for two days of hard marching. Of course, the Black Hats always pointed to Little Mac and said he first used the name in referring to the Western brigade. In all the early accounts after the war, it was always the “Iron Brigade of the West.” The men were proud of their Western origins. Over time and well after the war, the unit just became the Iron Brigade and the feud with the New Yorkers over the name was forgotten. The brigade lost its all-Western status shortly after Gettysburg because of heavy losses when a Pennsylvania regiment was briefly attached. Subsequently, other Eastern regiments were brigaded with the unit.

When did the unit take on the name “The Iron Brigade” and/or “Black Hats.” And can you explain the differences between the unit as The Iron Brigade of the West and how it came to be just The Iron Brigade? Why didn’t they keep it as an all western unit? The name “Iron Brigade of the West” began to circulate around September 1862 shortly after the battle of South Mountain. George McClellan claims he gave the unit the name, making a reference to “men of iron” while watching the Western brigade advance up the National Road toward Turner’s Gap. A newspaper reporter from Cincinnati was with McClellan and in writing about South Mountain a week later made a reference to the losses of what he termed “the Iron Brigade of the West.” The name “Black Hat Brigade’ was used earlier when the four regiments were outfitted with the Model 1858 black felt dress at the Regulars after the grey state uniforms were replaced in 1861 and early 1862. The distinctive hats made the brigade recognizable from both sides of a battle line. The Wisconsin, Indiana and Michigan boys liked the hats. Some two-year New York brigades first used the “Iron Brigade” name after an officer claimed they were made of “cast-iron” for two days of hard marching. Of course, the Black Hats always pointed to Little Mac and said he first used the name in referring to the Western brigade. In all the early accounts after the war, it was always the “Iron Brigade of the West.” The men were proud of their Western origins. Over time and well after the war, the unit just became the Iron Brigade and the feud with the New Yorkers over the name was forgotten. The brigade lost its all-Western status shortly after Gettysburg because of heavy losses when a Pennsylvania regiment was briefly attached. Subsequently, other Eastern regiments were brigaded with the unit.

So was it a name they were aware of at the time? How did Southern soldiers describe them as “black hats?” I think the name was used more often after Gettysburg. You find it in contemporary accounts by other soldiers and even some privately purchased identification tags that used the words “Iron Brigade.” The Wisconsin, Indiana, and Michigan men called themselves “the Big Hats,” and, of course, it was at Gettysburg in 1863, upon seeing them, that the Confederates called out about “those damned black hats” and “black hat devils of the Army of the Potomac.”

The Iron Brigade of the West had somewhat of an inauspicious start with regard to their organization and leadership, the men didn’t take to some of the first officers much? This could have unraveled the unit from the beginning do you think? I think the leadership troubles that beset the 2nd Wisconsin and 7th Wisconsin were typical in many states as they began raising regiments for the Union army. Governors generally selected the colonels and often used the rank to bestow favors or reward their friends. I think generally they tried to do the right thing, but the whole idea was new and they needed to sort it out. Gov. Alexander Randall of Wisconsin quickly made the changes needed and sought officers who would be successful. I also think that the ability of line officers in the companies varied, but they generally proved to be successful and became good leaders. The soldiers themselves recognized the worth of their officers and that determined the efficiency of each company and each regiment. The Iron Brigade regiments had some very good volunteer officers. With the risk of missing some of them, those that come quickly to mind include Rufus Dawes, Lysander Cutler, Edward Bragg of the 6th Wisconsin, Sam Williams and William Dudley of the 19th Indiana, Hollon Richardson and William Robertson of the 7th Wisconsin, Ed O’Connor, Lucius Fairchild and Tom Allen of the 2nd Wisconsin, and Henry Morrow of the 24th Michigan. Those are just a few and many others could be included in the list.

In your mind who are the most important leaders without notice to rank in the Iron Brigade? Who are your favorite? I mentioned some of them above. I am partial to Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin because he served bravely and with distinction and yet in modern Civil War studies gets little mention. Dawes wrote one of the most powerful memoirs of the war and deserves his own biography. I am also a big fan of Hollon Richardson of the 7th Wisconsin, who suffered six combat wounds, Lucius Fairchild of the 2nd who lost his arm at Gettysburg, and, of course, Johnny Gibbon, who brought so much to a brigade of volunteers. As for favorites, how can I not like James Patrick “Mickey, of Company K,” Sullivan of the 6th Wisconsin? He left a little body of writings that are enjoyable even today although, as many of Irish descent, he used light quips and clever language to cover a lot of anger. I had a chance to meet and spend time with his son and Sullivan the younger was much like his old man. But there are so many others to admire and you will find them in the book.

If we could talk to a member of the unit today and ask what battle was the hardest or toughest what would they say and why? Soldiers in different regiments would respond differently. For the 6th Wisconsin, the worst battle was always in the cornfield at Antietam. A man in the 7th Wisconsin might mention South Mountain when the unit was caught in a crossfire, or the retreat from Seminary Ridge at Gettysburg. For the 24th Michigan and 19th Indiana, it was probably McPherson’s Woods and the last stand at Gettysburg. A 2nd Wisconsin man would point to Gainesville or Brawner Farm as the regiment’s worst moment of the war. A volunteer serving with Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery would say Antietam when the battery was almost overrun.

I really liked your Postscript, can you elaborate on how and why you came up with the aspect of the Iron Brigade in Civil War memory? The Postscript was always looming because to carry the story of the Iron Brigade to the end you needed to tell how the war affected the survivors and what happened to them. I am interested in the idea of how memory affects the action of individuals. I think it is one of the most interesting sections of the book. The survivors walked in the long shadow of the war the rest of their days and it affected how they lived their lives in many ways they never understood. It was not always a happy memory and I think that became more acute as they aged. What had they accomplished when they were young? Was it worth all the destruction, suffering and loss as well as disruption of families and communities? They needed to find some sort of redemption from the war they were apart of in their youth and why it was important not only to themselves, but the nation. Some, not all, but some, found that absolution in preservation of the Union and in the end of slavery. But even those individuals recognized as well that there was a long way to go. They also worried the sacrifices of their generation would be forgotten and that led to the reunion movement, the erection of monuments, and the marking of battlefields. It was the story, I would submit, not only of the survivors of the Iron Brigade, but all the veterans of the Union army, and perhaps all American wars.

What’s up next for you, what are you researching and will it focus on another aspect of The Iron Brigade? I am working on a handbook on the Union soldier that gives a look at who was the fellow they called Billy Yank and how he lived and operated in the war. It provides a quick reference for the typical Federal soldier. After that, I have a couple of things I am considering, but I am not sure exactly which one will become the focus of the research and writing. Thanks for the opportunity to expand on The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory. I appreciated it

Add One